I remember the sports, ah, how I remember the sports. Of all the things I did back then, I remember the sports most vividly and, for the most part, with fondness.

I played baseball beginning in the junior-junior program sponsored by the American Legion and later in the junior division. I was an outfielder mostly, but for a time I played first base and pitched. I was an adequate outfielder with a pretty good eye for fly balls and I had a good arm. I was an adequate first baseman. I was a wild pitcher. I excelled as a hitter. Lloyd Hamre and I were the best hitters on our team. Lloyd was a switch hitter and could hit homeruns from either side. I was strictly a rightie, but I could hit it as far as Lloyd. We made the state finals twice, losing to Aberdeen the first year, and to a Black Hills team the second. I remember that last loss. We were way behind, like 12-2 with three or four innings to go. Then we caught up by picking away at the score. In the last inning we were ahead by one run. I was playing right field and a ball was hit to me with runners on first and second. It went through my legs. I retrieved the ball and threw it wildly toward home, but too wild and too late to prevent the winning run from scoring. I remember it so well because it was such a painful memory. I let it go through my legs, like a little kid just beginning the game. I threw it as hard as I could to home plate but with the haste and inaccuracy of desperation. And I lost the game for us.

I played football beginning in my freshman year. Before that we’d gotten our training with touch games in the park. As a freshman I played quarterback in the days before the T-formation became known, in what was then called a single-wing formation with the fullback four or five yards directly behind the center and two tailbacks on a diagonal right or left of the fullback, the quarterback one yard back behind the right or left guard. All the quarterback did was call the plays and the cadence for snapping and block for the runners. Now and then I would get a direct snap and take the ball on a quarterback sneak. I remember one play in a junior varsity game against the Cheyenne Indians where I carried it for about twelve yards up the middle. Under the tutelage of our new head coach, Bert Dent, I became a second-string lineman as a sophomore because I was still growing and we needed more meat in the line. I began as an end and I loved to catch the ball. If I was good at anything it was at catching passes. I was also good on defense because that didn’t require much thought or skill—just size and aggression, both of which I had. On defense in my sophomore year I remember scrimmages against the first team where I would have to tackle Howie Naasz, a senior who seemed to me to be as huge as a bear, with black black body hair and beard, and I hated it because he was so big and it was so painful to tackle him. But then Howie graduated and I got bigger and I was moved to first string offensive and defensive end in my junior year, to offensive and defensive tackle in my senior year. Our last two years we had atrocious records, losing far more than we won. We lost regularly to Minot, Belle Fourche, Pierre, Miller, and Ipswich, but we beat the hell out of Eureka and Gettysburg. I liked playing football but I didn’t love it. I hated calisthenics, I hated scrimmages on that dusty, cockleburry practice field behind the high school, I hated my helmet that would turn my hair orange every time I perspired, which was every time I wore it. I loved playing the games, even when we lost. I remember a game we lost to Miller, but a close loss. On a kickoff, Bill Sherman took the ball and I made a block for him, then got up and chased him down the field and made one final block that sprang him for the touchdown. I remember weeping a silent tear in the darkened car on the way home when I thought of how unjust it was that I’d played my heart out and we still lost. I remember a game against Ipswich in my senior year. Our coach had decided to use me as a running back occasionally. I took the handoff and swept around right end for fifteen yards. In the pileup one of my tacklers kept twisting my foot after the whistle and I open-handedly whacked him on the head. Fifteen yard penalty. I wasn’t used as running back after that. In that same game on defense, the Ipswich runner was going right along the line of scrimmage and he was boxed between two of our defenders. I was in the middle of the two and knew the runner would have to turn between them and directly at me. I got up a head of steam and met him in the opening for a spectacular tackle. I don’t know if we won or lost, but I remember that tackle. In my first year of college, I was recruited for the university football team where they made me a pulling guard. I hated it and stuck around for only a week or two. I had better things to do than be a second-string pulling guard for the USD Coyotes.

The sport I truly loved was basketball. Even today, over fifty years later, I still have occasional basketball dreams in which I’m popping fantasy jumpers from way out or soaring up for slam-dunks. In the late ‘40’s and early ‘50’s in high school, there were no such things as long jumpers or slam-dunks. I take that back. Jim Tays from Gettysburg could dunk the ball in warm-ups, but I never saw him do it in a game. And the long jumpers were long set shots, either two-handed or one-handed, but with both feet firmly planted on the floor.

Amazing, though, after all these years, that I would still have such vivid memories of some basketball games. I remember a specific shot I made in a game against Gettysburg in my senior year. I got a long offensive rebound just beyond the free-throw line and put it in from there, banked it in from directly in front of the basket. Obviously, I was pumped up and I missed the shot so badly that it went in. I scored fifteen points in that game, one of my highest totals, probably the highest total. Why would that particular moment in my life remain so vivid when nothing else about that game remains? I remember a fast-break basket I made in a blowout of Sisseton in the finals of the Class B regional tournament. We won by something like 82-50, and the basket came late in the game when I was trailing in the middle and took a pass from Fuzzy Baer, put it up underhanded and it fell through after bouncing around on the back of the rim.

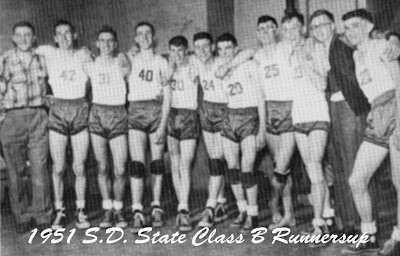

I can’t begin to figure out how many hours of my young life were spent on one outdoor court or another, playing pickup games involving anywhere from four to twelve of us. Or playing horse or one-on-one. Or spending hours all alone just dribbling and shooting. We met behind Jerry Hand’s house, across the street from Red Ochsner’s house, in the lot next to Billy Spiry’s house just two houses up from our house, on the court next to the junior high. Or on that sneak-in court in the high school gym. Hours and hours and hours. I played on the junior varsity as a freshman with Bill Sherman, Gene Schlect, and big Bill Campbell at center. There were others but I don’t remember who. We won more than we lost. I was moved up to the varsity when I was a sophomore and I played reserve guard. As a junior I was starting guard with Glenn Wessel, Fuzzy Baer and Wayne Todd at forwards, and Gene Schmaltz at center. We were small but we were quick. We even made it to the state Class B tournament in Aberdeen where we lost all three games and wound up eighth. But we played well in losing. We all decided that Wayne Todd, with his ball hogging and trying to score all the points, was the cause of it all. In my senior year, I and Bill Houck played guard, Bill Catey and Fuzzy Baer the forwards, and Gene Schmaltz the center, still small but scrappy, and we loved to run our opponents into the floor. We won the district and regional tournaments again, and again went to the state Class B tournament in Mitchell. I had been playing very well in the last half of the year and I was really excited about playing in the state tournament. My strength was always rebounding and defense and I remember especially two games during the regular season where my defense stood out. Against Ipswich I was assigned to guard their ace scorer. Bert Dent reminded me before the game that the Ipswich forward liked to spin around his defender to the inside and that I should overplay him to that side. I did, and I fouled him out in the first half with offensive charges. And in another game against McLaughlin I had to guard the vaunted Indian scorer, Teddy Ankle. Teddy was not unusually tall, but could, like most of the Indian players I’d ever seen, make shots from anywhere, usually with liquid hook shots. He usually scored between twenty and thirty points a game. I held him to ten.

But back to the state tournament I was so looking forward to. In the first game against Kadoka, right after the opening tipoff, I stole the ball from their guard and dribbled in for a layup. The defender shoved me from behind and I went into the stands . . . and felt my left ankle give way under me. That was the end of my high school career as a basketball player. I underwent diathermy treatments to reduce the swelling but to no avail, and I wasn’t able to get into any of the games. We won the first one against Kadoka with their giant of a center, and we won the second game against a team from Ethan. But we lost the final to Harold 50-46. I’ve always believed if I’d been able to play we would have won that state championship. Instead, Red Ochsner played in my place, even got to shoot the free throws I had coming after the foul that ended my career. That tournament, that sprained left ankle, that disappointing end to what could have been a glorious basketball conclusion will always haunt me, and I’ve spent most of my life wondering “what if?”

When I talk about sports, how could I ever overlook the one sport that has dominated my entire adult life—golf? I don’t remember exactly when I started golfing, but it had to be when I was eleven or twelve. My father, one of the prime movers behind building the Mobridge golf course, must have started me, but I don’t remember playing much golf with him. He was always busy running the grocery store. Most of my early memories of golf were solitary rounds played endlessly on summer days. I’d begin in the early morning and play all day, my goal usually forty-five holes. I don’t remember ever practicing much, just playing. And I don’t ever remember the course being crowded. I guess I must be remembering weekdays when all the adults in the community were working, and I was one of the few kids who played golf. David Duran was a year older and he and I seem to have been the only young golfers in Mobridge. I remember playing rounds with him in the early spring when the snow would still be up on the hillsides and melt water was flowing in the valleys.

The Mobridge Country Club was formed about when I was born, and my father would have been one of the founders. The course was laid out over the rolling hills north of town, high enough to overlook the river and railroad bridge two miles below and to the west, Oak Forest (a tiny plot with some twenty or thirty oak trees) midway between. Nine holes measuring about 2900 yards, most of the holes following valleys with deep rough on the side hills. The rough was cut two or three times a summer, and just before it was due to be cut would be up around the knees. Wild prairie grass and flowers just waiting to swallow a stray golf ball. I remember spending hours wandering those grassy hills looking for balls, the joy of finding a reasonably uncut Titleist or Spalding Black Dot, or a Club Special, that wonderful ball the Acushnet Company put out for fifty cents. More often, though, I would find balls with cuts so deep the wound rubber was exposed. Those balls cut so easily back then that any mis-hit usually went right to the quick, and another dollar or half-dollar was down the drain. Often when I found a ball cut deep enough, I would, with fingers and teeth, strip off the hide, down to the layer of wound rubber, which I would then unwind by rolling it out in front of me, until the rubber windings ran out and I was down to a blue or green interior ball filled with some nasty viscous white fluid. The purpose of this exercise wasn’t to accumulate blue or green rubber balls. It was just to do it. Isn’t it odd that we paid nearly as much for golf balls then, over fifty years ago, as I’m paying today, and for vastly inferior balls then. And I couldn’t unwind any balls today, the outer skin being so much tougher, the number of solid-core balls being sold today so much greater.

After the mowers made their swipes through the knee-high roughs, the grass would be piled in haymows until it dried and could be picked up. And rattlesnakes loved to curl up under the hay. A lost ball anywhere near one of those piles of hay would remain lost, just as a ball that went down a gopher hole, which might also be a snake hole. Natural buffalo grass comprised the fairways and grew sparsely, in clumps. Winter rules allowed one to move the ball anywhere within reason onto one of the clumps. Nature was the watering system; therefore, often in July the fairways were baked hard as stone and drives would go forever. But too often, forever meant deep into that knee-deep rough. The greens were small circular sand greens, made with oiled sand in a prairie dish, sand to a depth of about six inches, the cups permanently in the middle, the pin a short steel rod with a tubular top for smoothing out a path from ball to cup. I can still smell the motor oil they used for treating the sand greens, still feel the slickness on my hands from that inescapable oil. How we ever kept our hands from slipping on the grips I’ll never know.

I never practiced, I never had a lesson. I grew up playing on that strange little layout in north central South Dakota and never knew until I was much older that there was anything better. My best 9-hole score there was 33. I don’t remember my best 18-hole score because we almost never kept track of such numbers. Golf was intended to be played in 9-hole increments, and 33 was the best number I ever shot there. I think I must have done it more than once but I’m not sure. I can’t remember what kind of clubs I began playing with, probably some of my father’s castoffs, hickory-shafted niblicks and mashies and midirons with maybe a brassie and a spoon. Don’t I wish I had those clubs today. I think my brother Dick must have most of them. For Christmas in 1947 or ’48 my parents gave me a set of clubs. I remember seeing what had to be a box of golf clubs under the tree and I was as excited about that present as anything I’ve ever gotten, before or since. I opened it and it was a beginner’s set of Louisville Slugger irons—3, 5, 7, 9, and putter. I was crushed and my face must have shown it. I wanted the irons, yes, but I really wanted the woods. Even then I was more attracted to distance than to accuracy. My father may have taken some perverse pleasure out of my disappointment or he wouldn’t have hidden the other box, maybe anticipating my ingratitude. I hope that wasn’t the case. He then gave me the box with the woods, a driver, 3-wood, and 5-wood. And they were beautiful—reddish brown persimmon heads with steel shafts. I played with that set all through high school, and when I returned from Korea and went back to the University of South Dakota in the fall of 1955 I played on the university golf team with that set, eight clubs in all, my golf shoes an old pair of my father’s a size and a half too small, the spikes worn down to smoothness.

John Enright from Sioux Falls, our number one player, was twice a winner of the South Dakota State Amateur. That's him just to the right of me. He must have gotten quite a laugh at the Mobridge hayseed with only eight clubs.

Before that, before I finally golfed on grass greens and full-length courses, before I was exposed to the rarified air of Aberdeen and Sioux Falls country clubs and country clubbers, I golfed in Sunday tournaments in Mobridge and other towns around the area on courses equally as strange as the one in Mobridge. I once golfed on the course at Cheyenne on the Sioux Indian reservation west of the river. It, like the football field I once played on, is now under several hundred feet of Oahe water. I golfed several times at the course in Eureka. And once with my brother Dick in Bowdle. These were odd little tournaments usually dominated by some hotshot from Aberdeen who, for whatever reason, felt he should come to the South Dakota hinterland to win a dozen golf balls and a trophy for first place. I never won any first places but I would often win a flight prize. The flights were never based on handicaps because back then we didn’t know what handicaps were. You were flighted by whatever score you made on the front nine, then placed according to how you did on the second nine. It seems to me that such a system would be open season for any sandbagger who wanted to win a flight prize. I grew up in an age when there was no national exposure to golf, no television, nothing much in the news. At least not much that came to my South Dakota attention. I did know about the Bauer sisters, Marlene and Kathy, who both played on the LPGA, because they had originally come from Eureka. But they were the only professionals I knew about. I didn’t know who most of the male pros were although I must have been aware of names like Snead and Hogan. I didn’t even see my first grass green until I was twenty-two and began playing golf for the University of South Dakota.

Golf at USD was in its infancy. We played in a conference consisting of small schools in South Dakota and Iowa, and we were on a very limited budget. There were five or six of us, and we played positions determined by how we had played in the previous match. I remember being medalist in one match on our home course with a 75, so I must have been shooting reasonably well with my 8-club set. My putter was a gooseneck with ersatz wooden shaft. I still have it, although I haven’t tried to putt with it for over forty years.

I played on the team my last two years in college, and my spring grades invariably dipped as golf season began. I just couldn’t do both, and of the two, golfing or studying, I did what I most enjoyed—golfing. I even went on to play in two South Dakota state amateurs with that same incomplete set of clubs, one in Aberdeen where I made it to the finals of the first flight, and one in Sioux Falls where I did so poorly I can’t remember where I stood. I assumed I would be doing that for the rest of my days in South Dakota, going to every state amateur, but I made only one more after I and Rosalie were married, the 1961 tournament in Watertown where I played with a complete set of used clubs I bought in Redfield shortly after we got there. Rosalie went with me and didn’t have much of anything to do while I was golfing, and the expense was hard to justify. Thus ended my pursuit of the state amateur crown. But golf continued to be my main obsession for the rest of my life.

HELL YEAR - 1951-52

In September of 1951 Norma went away to school to become an airline stewardess and I went to the University of South Dakota to become an archaeologist.

During that awful first year of college I don’t remember seeing her at all, never on a visit to the university to see me, not on the vacation times I spent in Mobridge. Maybe those times never coincided, hers and mine. I don’t remember ever exchanging any letters with her. I know I never dated anyone at college. I know I drank a lot. I know I spoiled that first experience in college with my immaturity, my shyness, my drinking. I pledged to the Phi Delta Theta house shortly after I got there, and that was probably an unwise decision. I’ve never been much of a joiner, and that affiliation with a fraternity when I was still seventeen was a mistake. It took too much of my time and attention and took me away from studying.

The Phi Delts had a reputation as the party house, the drinkers and rowdies. It was not a good choice for a young man who already had a drinking problem. It, like the year before, was a disastrous year that I’ll always look back on with extreme regret.

Typical of what went wrong was my experience in freshman English. Or, more accurate, my inexperience in freshman English. I was always a bright, though not a very proficient, student. I was supposed to write essays in that English course and I didn’t have a clue what an essay was. I don’t remember ever having done much writing in high school. I know I was totally unprepared for what they were asking me to do in college. One of my first essays was called “My Dog, Rusty.” Doesn’t that sound like something a sixth-grader might write?

I had a natural aptitude for foreign language (despite my awful Latin grades in high school) so I did all right in Spanish. I was always good with math so I did all right in first year math. I had to take an introductory course in geology, and I guess I must have done all right in that. By all right, I mean mostly C’s in that first semester.

Then the second semester began and things got even worse. We went through hell week at the Phi Delt house, a week of brutal initiation to the mysteries of a frat house. A weeklong test of our wills to see if we really wanted to join. It involved a week of no sleep, various exercises in humiliation designed to make us or break us. I’ll briefly describe some of those tests as I remember them. First we had to make for our Big Brother, our sponsoring frat brother, a pledge paddle, a paddle he would use on us occasionally to see how much physical pain we could endure. Early in the festivities they took us to the downstairs dining room, made us strip naked, smear our anuses with peanut butter, then crawl through an obstacle course in a long line of naked bodies, our noses positioned between the buttocks of the pledge ahead of us. Then we had to eat two mouthfuls of a disgusting concoction that contained as many awful ingredients as they could come up with. I never learned the recipe, but I know part of it was raw eggs (including the shells) and a wild assortment of spices, the main one being curry powder. I’ve never since been able to smell curry without a gag reflex. I don’t know what the binder was. I never wanted to know. I remember that whatever was in that mixture was disgusting enough that it took all I could do to swallow two bites of it. Another time we were made to consume large doses of X-lax and swallow a kidney medicine that turned our urine blue for several days.

Sometime after midnight, on the last night of hell week, we were taken out—naked, barefoot, blindfolded—for a ride to a nearby river where we were going to jump in and swim to the other side. Or at least that’s what we were told. It was a little like the snipe hunt I went on when I was at Boy Scout camp on Bigstone Lake. The car ride took nearly twenty minutes of turns and twists. Then we stopped and were led from the car across wet grass and weeds to the bank of the river. All together, at one brother’s signal, we were told to jump feet first into the river. I guess I didn’t hear the feet first requirement or maybe I was just too nervous and scared, not being much of a swimmer. I dove headfirst and landed on my head and stomach on the recently watered lawn in the back yard of the Phi Delt house. I ripped off my blindfold and could then see the hoax for what it was. And hear the laughter of the Phi Delts who’d gathered to watch the show. I had a headache for a few days and the cuts and bruises on my body healed eventually. And I had passed the test and was allowed to become an active, a Phi Delt. Whoopie. I was never involved in that initiation ritual as an active, never could have brought myself to it, and I’m sure that not many years after I went through it, such rites of passage were banned forever on all campuses in the country. Good riddance. Aside from the brutality and inhumanity of the week, it was also a week during which there was no possibility of doing any kind of schoolwork. Two people I knew from high school decided to go to the university with me—Dorothy Denoff and Jackie Hepper, both of whom pledged Alpha Phi, the most popular sorority on campus. I didn’t see much of them, but I remember that Dorothy congratulated me on my singing in that year’s Strollers Show. Every year the Strollers, a group of artsy upperclassmen, would sponsor a variety show in which each student group would put together a ten or fifteen minute act or show to present, with the Strollers voting on the three best acts. The Phi Delts did a silly skit that actually involved me giving the punch line to the old joke about the bear and the ice hole, how one might avoid the danger of the angry bear by kicking him in the ice hole. I can’t remember what song I may have sung. It was my first public appearance and I can’t remember much about it except that Dorothy told me I had done well.

That was maybe the only thing about my freshman year that deserved any accolades. I may have been an active fraternity brother, but I was a dead duck as a student. I remember finally giving up the ghost with a hundred days left in the school year. For the most part I stayed in my room, reading, listening to music, carefully marking off another of the hundred days. No one told me I could have gone to the administration and dropped all my classes. I was too ignorant to think of that. I knew only that I hated it there in Vermillion in that fraternity house. I wanted only to get the hell out of there, beat my grades home, sneak them out of the mailbox before my parents could see them. And after that I didn’t know what I was going to do. There was a war going on in Korea and young men were being drafted, so I guess I assumed I would wait for them to call me up.

I didn’t manage to keep my grades hidden from my parents. I don’t remember what they said to me about my aborted year of college. I know they must have been terribly disappointed, but I don’t remember ever being told that. I must have simply blocked it out of my mind. Even a patch of fictional putty wouldn’t help that flawed year of my young life.

KOREA

The summer of ‘52 summer was the summer of the awful job my father got for me at the Mobridge Wholesale House, the summer of the truck, and it was a dismal continuation of the preceding year in Vermillion. But it also held an on-again segment of my romance with Norma DeSart.

I dated Delores Stoecker a few times that summer, but I remember vividly one day driving past the First National Bank building on lower Main Street, knowing that Norma was working there for the summer. I remember nearly breaking my neck trying to see her through a side window on First Street. Nearly having an accident with a car coming at me because I wasn’t paying attention to where I was going. She told me later she’d seen me and thought it was hilarious. That must mean that we began going together for the remainder of that summer.

Bill Catey talked Lloyd Hamre and me into joining the army instead of waiting to be drafted. I can’t remember what his argument was, probably why not get it over with instead of waiting around for it to happen. So that’s what we did, and on September 21, 1952, the three of us were sent to Illinois for our enlistment physical and assignments to a basic training site. Hamre went somewhere else and Bill and I went to Fort Breckenridge, Kentucky, for the sixteen-week training.

Fort Breckenridge was the home of the Screaming Eagles, the 51st Airborne Division, so that was the patch we wore on our uniforms. But neither of us had any desire or intention of climbing into a parachute and jumping out of a plane. The camp was just across the Indiana border, not far from Evansville, Indiana. The climate was supposed to be benign at that latitude, but the three days we spent on bivouac were three of the coldest days they’d ever had there.

I wasn’t very fond of those days in basic training. I was never one who enjoyed being told what to do, especially when I had no chance of saying anything back. The army doesn’t care much for men or boys who talk back. Another minor problem was that Catey and I were two of the very few enlistees in camp. Most of the others were draftees. I was RA17371511, the serial number I had to shout out any time an officer asked for it. The RA stood for regular army, letting everyone know within shouting distance that I was one who had actually volunteered to be there. The draftees all had serial numbers beginning with US.

The most vivid of my memories are the smell of burning coal and the constant raining down of coal ash from the furnaces in each building.

I remember days on the rifle range: “Ready on the right! Ready on the left! Ready on the firing line!” And then we’d shoot in prone, sitting, and standing positions, getting our scores sent back by phone. I was an average marksman. I learned how to break my M-1 down and put it back together again with my eyes closed.

I remember crawling through the obstacle course with my M-1 cradled in my arms, barbed wire overhead, machinegun fire zinging above.

I remember days on KP and how much I hated them. They were like the hazing in the frat house, nonsensical acts intended to humiliate and demoralize the hazee. The person on KP was at the mercy of the cooks. It was my job to fire up the coal stoves, help prepare the meal of eggs or chicken or s.o.s, and then help serve it. And after the meal, that was when the ugliness began. Seemingly hundreds of pots and pans needed to be washed and wiped. The stoves had to be meticulously cleaned and prepared for the next shift. The concrete floor had to be scrubbed and scrubbed and scrubbed. Until finally, the head cook would call it quits and let us go back to our barracks to bed, usually well after midnight.

I remember having to man a corner of the stockade wall with rifle at the ready to prevent any escapes. I wonder what I’d have done if I’d actually been involved in an escape attempt. Probably poop my pants.

I remember the morning calisthenics, almost identical to the workouts we used to have at football practice. Hated equally in both places.

I remember the twenty-mile marches, with full gear.

But most of all I remember bivouac. Bivouac was a three-day exercise in field maneuvers, complete with squads having to follow a course from point to point, set up outposts, all the fun details of life in the field during battle. We were each issued a small pup tent for the nights and a single-blanket sleeping bag. It was made of one army blanket with a zipper. That was it. Normally, Kentucky winters were mild enough that a single layer sleeping bag would have been adequate. But our first night out, a freezing rain fell . . . all night. My pup tent was just that, a piece of canvas pegged down on the sides with a back flap and a front flap that tied together to keep out the wind and cold. My floor was the ground. The zipper on my sleeping bag was broken and wouldn’t zip. So all that night I slept on the ground in that unzippered sleeping bag, tossing and turning on that hard lumpy ground, freezing my ass and every other part of me. I don’t remember ever being before or since as cold as that. In the morning I got up groggy, untied my front flap, and discovered that I was frozen in an icy cocoon. We all had to break our way out of our tents, like pupae emerging from their chrysalides, into a Kentucky morning brilliantly coated with ice—the ground, the trees, the bushes, the weeds. Everything. And then the sun came out and the ice started to melt and shatter. As Frost described it in “Birches”: “Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away / You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.” It was beautiful. But we were all too cold to appreciate the view. I remember having bought beforehand a box of 24 Baby Ruth candy bars and consuming them all within that first day. For the most part I hated bivouac, I hated basic training, I hated the army. Do I sound like a spoiled, mewling baby? I guess I do.

I had two major disappointments while in basic training. Near the end of the sixteen weeks, we were asked where we would like next to be assigned. I put in for a guided missile school in Texas. I had enough math and science in high school and college (even though a bit shaky in college) and good enough test scores to make it almost a shoo-in. But I had crossed the P.F.C. who was our company clerk. I had taken some M1 cartridges, pulled out the slugs, emptied the powder, and reinserted the slugs. I had about three for souvenirs and kept them in my footlocker. They were found during an inspection and assumed to be live ammo. I was never allowed to explain, just reprimanded. And when I put in for the guided missile school, the clerk-typist conveniently lost my application, although he denied it. And when the assignments came out for our next tour of duty, Catey and I were on the list for Germany. Whoopie! No Korea for me. But the next day they came out with a revised list, one that separated the Germany roster from the Korea roster by alphabet. Catey to Germany, Travis to Korea. I really didn’t want to go to Korea. My images of Korea were all shaped by the news and the devastation war involves. All I could envision were bombs, fire, and screaming hoards of North Korean and Chinese troops rushing to cut me down in my youth.

In early February, I came home for two weeks before shipping out. I entered Mobridge like a Viking. I was splendid. I was resplendent. I felt peacock proud in my dress khakis, cap, bloused trousers, gorgeous paratrooper boots. The boots were not army issue. I’d bought them at the PX for forty dollars—spit-polished cordovan with zippers up the inside for ease of donning. They were truly handsome, and I felt truly handsome in them.

Norma was in town doing I can’t remember what. Maybe the airline school thing had fallen through and she was there still working at the bank. I can’t remember. But I know we were reunited, and we said things about marriage. No ring, understand, but definite marriage talk. I guess I must have felt safe enough with such talk since I was about to go away for who knew how long—nine months if I were sent directly to the line, sixteen months if I were assigned to the rear. Forever if I were killed, a distinct possibility in my mind.

The two weeks rushed by and then it was time to report to San Francisco for shipping out. David Bergstrom, a high school classmate, was home, also in the army, and was also supposed to report to San Francisco. He convinced me that we didn’t have to report on the date our orders called for, that lots of others had taken their time and delayed in San Francisco for as long as a week before reporting, that nothing ever happened except for being put on a later ship. One could always say one was delayed by an illness or a death in the family. I believed him. Maybe because I wanted to believe him.

We flew to San Francisco, rented a hotel room, and spent the next week drinking in one San Francisco bar or another. I remember my drink of choice then was a whiskey sour, lots of whiskey sours. I can still taste that grapefruity sour taste mixed with cheap bar whiskey, the orange slice on the side, the stemmed cherry on the bottom. We drank a week’s worth of them but didn’t see much of San Francisco. I did take a trip to Treasure Island to see one of my friends and classmates Gene Schlect, serving there as naval clerk typists.

Then we could delay no longer and we reported to our stations, he to his, I to mine. The good news is that I wasn’t reprimanded, the bad news is that I missed the ship all the other Breckenridgers were on, and was put on the next ship out. My buddies from basic training had all been assigned to a quartermaster corps in Tokyo. I was assigned to the 65th Infantry Regiment in the middle of Korea. I was going as a private E-2 rifleman in a unit 50% Puerto Rican.

The ship was a large gray troop transport with several thousand of us aboard. I’d bought a tiny camera in San Francisco and remember taking pictures of the Golden Gate Bridge as we passed under and away from it. Within hours the seas became stormy and the boat rock-and-rolled for a day and a half. Most of us spent those first forty hours throwing up in the urinals below deck. We weren’t allowed to go on deck because it was too dangerous. So, for lack of anything better to do, we slept in our bunks stacked four up with noses nearly touching the bunk above, ate little or nothing, and threw up at regular intervals. The astringent, sour stench of vomit permeated the ship. The johns were literally awash with our leavings. But after forty hours the seas calmed, our stomachs settled, and we were allowed to go on deck to sit throughout the day. In fact, unless we were sick we had to go up. I remember the smell of the ocean, the constant breeze, the feel of the gray steel everywhere coated with an unpleasant slime from the salt in the air. We read or played endless games of poker or pinochle or gin rummy or solitaire, or we just stood at the rail and watched the ocean and the sky. We saw schools of porpoises chasing alongside, skimming the surface and soaring above. We watched flying fish shoot from the water like bullets, sailing along with us and then plunging back into the sea. I watched clouds and sunrises and sunsets. There’s more sky on the ocean than even South Dakota has. I thought about Mobridge and Norma.

I think I must have written her several letters telling about my experiences getting to Korea. I know I wrote her fairly often all the while I was in Korea. This must have been when I first started enjoying the art of writing, of keeping track of events and sensations in my life. I know we exchanged love letters. Romance is so much easier to carry on through correspondence than in social and physical contact. At least for me. I’ve always been able to say things in letters that I’d never say face to face. I guess the distance gives me a certain immunity to my nerves, gives me time to think out what I want to say, gives me a freedom to become someone I’d like to be rather than who I am. And it also eliminates two-way conversations. There’s safety there. One of the first letters I received from Norma after I was finally established in a spot with a real mailing address reported that she had talked Mary Ellen Bailey into flying with her to San Francisco to see me before I embarked on my voyage. They arrived there the day after I shipped out. I now know that if I’d still been there, we would have gotten married. Whether I’d wanted to or not, we’d have gotten married. A lifetime later, in 1991, when we were back in Mobridge for my mother’s ninetieth birthday, I saw Norma again. I didn’t recognize her at first. She was fat and gray. But aside from her looks, I knew then and had known for a long time just how bad a mistake my marrying her would have been. Talk about bad marriages. We’d have made such a lopsided couple. But at nineteen I could see people only through a romantic’s eyes. Our reunion and union in San Francisco would have made such a romantic plot I wouldn’t have been able to resist it.

Two weeks aboard that troop ship, a bored soldier docked in Tokyo Bay, then took a short train ride from Yokohama to Tokyo where I went through the line in the quartermaster unit, was given a duffel bag full of all the equipment I would need in late winter Korea—the sweaters, long johns, socks, underwear, parka, Mickey Mouse boots, helmet, helmet liner, gloves, pants and shirts and jackets, down-filled cocoon sleeping bag (a great improvement over the one I had during bivouac), infantry boots (no more the beautiful cordovans). I was greeted there by all those with whom I took basic training, who had been assigned to the quartermaster corps remaining in Japan, greeted raucously and jeeringly because I’d missed the boat, so to speak. I think I simply shook my head in disgust and kept going.

From there I boarded a train to the northwest coast of Japan on the Sea of Japan, boarded another troop transport, and a day later put in at Pusan Harbor. When I got off the ship, I had my first scent of Korea, the ripe shit smell of the honey buckets, an aroma that pervaded the peninsula all the while I was there, and after a few months I became so used to it I no longer noticed. We were taken almost directly to a train station and told that we might want to keep our heads down on the train ride because of the sniper fire of infiltrators along the way. I really didn’t want to hear that. The ride by train was long and winding and slow, and, thank god, without any sniper fire. We finally got off somewhere northeast of Seoul. I and about twenty others were then put in the back of a deuce-and-a-half, a two and a half ton truck used to transport troops and supplies across rough terrain. We went up and up, grinding slowly up the mountainside, one-way traffic on roads that in the states wouldn’t even be considered roads.

Early on the evening of March 14th, I got off the truck and became part of the 7th platoon, 65th Infantry Regiment, Third Division, in the middle of Korea, just south of Papa San, a huge mountain overlooking most of central Korea. We were then about ten miles south of the 38th parallel in a section called the Iron Triangle.

I spent the first month there biding my time, our unit serving as backup for the forces on the line. I learned how to get along in the Korean climes. The nights were chilly but not really cold, and I had a potbelly stove and my expensive sleeping bag to keep me warm. I met a tall gangly young man named Mo Goodspeed, from Binghamton, New York, who became a good friend and was in the same outfit with me throughout my time in Korea. Sometime in that first month I made P.F.C., with a minimal raise in salary. The raise in rank was not for anything I’d done but simply for time in grade. Then sometime in early April they asked for volunteers to carry a BAR, a Browning Automatic Rifle. I volunteered. I’m not sure to this day why. Everyone knew that the first person in a squad to be picked off was the BARman. I was young and stupid. Soon thereafter I was made a corporal (not time in grade this time, this time for stupidity and the BAR).

Several weeks later Mo Goodspeed and I were transferred to the I & R platoon in the Headquarters and Headquarters Company of the 65th Infantry Regiment, leaving my BAR behind but keeping my corporal stripes. I don’t know why I was transferred there. “I & R” stood for Intelligence and Reconnaissance, which meant I was in a platoon that manned surveillance outposts one to five miles ahead of our lines or went on reconnaissance patrols to determine enemy troop strength and placement. The platoon sergeant was a mixed Japanese/Hawaiian called Pop Ferrar. He was an easy commander, and he loved to cook rice and chicken on the potbelly stoves we had in our tents. His skin was tanned leather, his face unlined by care or years, his laugh easy. He was our pop, and we had an easy time of it for those first five or six months. There were only about sixteen of us in the I & R platoon, all young and ignorant, all wanting only to get through our nine or ten or twelve months of rotation time (2 points a month for behind the lines, 4 points a month for on the line, 36 rotation points to get the hell out of there and rotate back to the states). Because I was the only corporal in the platoon, I was a grade ahead of the others who’d arrived when I did. So I was sort of second in command to Pop, and when he was transferred home to Hawaii, I was made platoon sergeant, a position I really didn’t want. But that didn’t happen until just before the war ended. Our platoon leader after the war was a strange young man from Puerto Rico named Lieutenant Garcia. He was as green as I was, and neither of us really knew what he was doing.

But before my assuming the role of platoon sergeant, there was a period of about three months when we were doing our I & R thing. I remember being assigned to a lookout bunker about seven hundred yards ahead of our lines. Our job was to sit in the observation slot with a 20-power telescope and keep track of enemy movement, take a count of the number of enemy we saw scurrying along the open portions of their trenches. Most of their movement was in underground tunnels, but some of it was exposed. The mountainside across the valley from us was bombed to desolation, no vegetation of any kind growing, just a brownish hillside with enemy troops scrambling along every so often, looking very much like ants on an anthill. Now and then we would fire an artillery barrage on the mountain doing no apparent damage. But I’m sure there must have been some underground death and destruction. One afternoon I watched our troops attack and capture a small hill below our lookout point about halfway across the valley. Through my 20-power scope, I watched the action like a movie just for me, front row center. It was far enough away to seem unreal, but I knew it was real because I could see men firing weapons at each other, men, both theirs and ours, falling to the ground. The hill was taken. We kept it for about an hour and then pulled back. I always wondered what purpose that attack served. To this day I can’t think of any reason for it, other than possibly to alleviate some general’s boredom.

After one of our several bugouts (hasty nighttime moves of the entire camp from one location to another) two others and I were assigned for about a month to a different lookout post. We stayed there for the entire time, dining on C-rations and assault rations, sleeping on cots in the bunker. I remember mice racing around on the ceiling canvas overhead. We could see their feet as they ran across and when they’d stop we flipped them up with a finger, bewildered silence, then a run for the side of the bunker. They could never figure out who or what was disrupting their travels, some cruel underworld god getting back at them for their mousiness. Not much else for entertainment in a bunker. We did, however, have a deck or two of cards, and it was there I first learned to play the only game of solitaire worth playing. The cards are placed face-up in nine rows, nine in the first row, eight in the second, etc. That takes 45 cards with the last seven used anywhere and anytime needed. The idea is to move the cards one at a time to other locations (black queen on red king, red jack on black queen, etc., just as in the more conventional solitaire games). But you have to spend as much as twenty minutes studying all the possible moves before you start moving, because once a card is moved that’s where it stays. The aces go up as in any solitaire game. The idea is to get as many columns open as possible to be used as transfer stations. Usually once the cards are all lined up in order the game is won. And if you study the moves long enough almost every game can be won. Not all, but most. I remember spending hours playing it, and I had hours and hours available. Our meals were a combination of C-rations and assault rations. The C-rations came in a carton with a sixteen-ounce can for the main dish. As I remember them, the variety wasn’t all that great. Some meals were better than others. One of the worst was sausage patties in a kind of greasy gravy. Baked beans was another I didn’t care for. A couple of the good ones were boneless chicken and corned beef hash. The chicken was everyone’s favorite and we’d all keep our fingers crossed hoping to strike it chicken rich. I’m sure there were other kinds but I don’t remember them. Along with the main meal we got a bread cracker, a round dessert of either orange or lemon jelly or a fudge-covered caramel bar, a packet of instant coffee, and a round patty of cocoa. Also in the package was a small pack of toilet paper, several four-packs of cigarettes, and a small can opener that worked like a charm. The can opener was only the size of a quarter, with a sharp metal cutter snapping up and away from a flat piece of metal. You cut into the can with a twist of the fingers then moved the cutter toward you as you flipped it up and down. Like magic. I wish I’d kept one for a souvenir. When we decided it was dinnertime, we’d go to one of the ration cases in the corner of the bunker and take a box. The boxes had no outside clue as to the kind of meal it contained, and it wasn’t fair to take one and then put it back. Once taken, it was yours. And it was always, like a lottery, a surprise to see what you pulled out of the case. You lost if you got the greasy sausage patties, you won if you got the chicken; you lost if you got a jelly bar, you won if you got the caramel bar. The assault rations were a special treat and we didn’t have them often. These were small flat boxes designed to be carried in a backpack by troops involved in an assault on an enemy position. A soldier would carry only two or three of these meals because the assault was for only a short duration and not many meals were needed. In the box was a small can, about the size of a tuna can, with the main entrée, all excellent—ham and eggs, turkey, roast beef hash, sliced beef or sliced pork in gravy. Again, there must have been other selections but I can’t remember them. Along with the can were a cookie, a cracker, and an instant coffee. And more cigarettes. If you weren’t a smoker before you got in the army, you soon became one. If for no other reason than to combat the boredom. The fellow bunker mate who taught me the game of solitaire was a French inhaler, and I can remember him for hours at a time smoking, drawing the smoke in his mouth, then letting it creep out like snakes from each side of his mouth to enter his nose. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone else smoke like that. How do I even know it’s called French inhaling? I don’t know. Maybe that’s what he called it. The only really memorable thing that happened while we were there was a visit from Major Eisenhower, the son of Dwight D. He was out touring the front and stopped to chat with us for ten minutes or so. He looked exactly like his father. It’s nearly impossible to put my time in Korea in a chronological sequence because I just don’t remember when certain things happened. The only thing I’m sure of is the demarcation between my Korea during the war and my Korea after the war. So I guess I’ll fill part of this in with impressions, regardless of when they took place.

I remember a night when I was the only one in my tent and we were under an artillery barrage. I was under my cot and I could hear the rain of shrapnel on the tent roof. I wrote Bill Catey a letter as this was happening, I guess to impress him with my imminent danger. Actually, I didn’t feel very threatened at all. I suppose an artillery shell could have found my tent, but I must have felt the odds in my favor, about like jaywalking a street in heavy traffic.

I remember a time when several of us were in a jeep and had to cross a piece of terrain that was under mortar fire. We decided to time it to make a run for it just after a mortar shell landed. So we gunned the heck out it and got around a rock outcropping to safety without being hit.

I remember one evening as I was dozing in front of the observation slot in one of the forward bunkers, a shell landed no more than ten feet away and woke me up immediately. I don’t think I dozed much after that.

I remember going on night patrol and some of us getting separated from the others somehow. My friend Chuck Cavallero, thinking we were sneaky gooks, nearly killed me when he fired his M-14 carbine at us in the dark.

I remember one spring afternoon when our whole patrol took a hike down to the river for a swim. I didn’t know the name of the river then and I don’t know it now. It was usually an innocent little rivulet that cut back and forth between high banks as it wound its way to the southeast, the hulking mountain called Papa San just to the south. But this day it was swollen with spring rains, muddy water flowing more swiftly than usual.

I was never a good swimmer and always felt some trepidation at the idea of water over my head. But I went swimming that day and nearly died. I was in Korea for over four months of war and that was the closest I came to death. It always remained so vivid in my mind that years later I wrote a story about it called “The River.” I tried several times to get it published but the market for short stories had by 1980 almost disappeared, especially for stories about Korea. The only taker I ever found was an Alaskan magazine called River Stories. But I think the publication must have gone belly-up because I never again heard from them after I got their letter of acceptance.

Other than that ill-advised swim in a river we’d been warned about, I was never seriously threatened with injury or death. None of my friends and acquaintances were injured or killed. The only person I had any contact with who was killed was our first platoon leader, a lieutenant whose name I’ve forgotten. His death was ironic because it came right at the end of the war, after everything but the signing of the documents had taken place. Both sides were getting rid of artillery shells in those final days and there was a terrible raining down of artillery and shrapnel from both sides. It was during this dumping of ammunition that he was killed. Then the signing at Panmunjom on July 27, 1953, the establishment of the 38th parallel as the line between South and North Korea, and the end of the war that was never acknowledged as a war. People still refer to it as a police action. Well, it was fought for over three years, over 54,000 Americans died, over 103,000 were wounded, and if that’s not a war, then we never before or since fought one. Granted, it didn’t seem to settle anything except to say to the communist regimes in China and North Korea they couldn’t militarily take over people and nations. Granted, the lines between South and North Korea were the same as they were before the war. Nevertheless, it was a war.

I had 16 rotation points when the war ended, and if it had continued I would have come home five months from then, just about the end of the year. But with the war’s end, the rotation system was replaced and I wound up staying another year, shipping out in July of 1954.

My impressions of Korea after the war: bombed out mountains, green valleys and rice paddies, the smell of the honey wagons distributing their loads on the rice paddies, the poverty of country peasants living in mud and grass huts. We had basketball hoops set up and played games with whoever was available. We played horseshoes in pits set up just outside our platoon tent. We played endless double-deck pinochle games. From somewhere, two fencing foils showed up and we took turns playing Errol Flynn and Zorro. I smoked, I grew a beard, I read novels, I wrote song lyrics, I wrote letters to Norma and my parents. Sometime in 1953 I got the “Dear John” letter we all joked about, the recipients of which were made miserable by the universal kidding. Norma had met and fallen in love with someone not from Mobridge, someone I’d never met. She was sorry, but life was short and I’d been away too long. I think I may have been devastated. Or maybe I was relieved. I don’t remember.

We drank beer, we drank booze. I remember drinking way too much whiskey on New Year’s Eve, 1953. I don’t remember much of what I did during that drunken party, but I must have had a huge hangover the next day. We had inspections, we had company dress reviews, we were bored out of our minds.

I went to Japan on R. R. for a week shortly after the war ended, to Fukuoka City. Rest and Recuperation. It was really a week to find a hotel room, get a girl, and drink and party for a week. My “girl” that week was Reiko, and she was probably not much older than I was, maybe twenty to my nineteen soon-to-be twenty. She could speak enough English barely to get by, but the others and I weren’t there to make conversation. It was a place for learning about sex, something I had no knowledge of except with Mobridge prostitutes. That’s pretty much all we did while we were there—slept, ate, drank, and made love to our “girls.” I went on R. & R. again in the spring of 1954, again to Fukuoka City, this time to a different hotel, one that my girl insisted was the best in town. Her name was Seiko Furui, and I truly thought I was in love. She spoke excellent English and she and I actually spent time conversing. She told me about her family and I told her about mine. I remember drinking lots of German and Puerto Rican beer, eating hamburger steaks with a soft-fried egg on top, going sightseeing with Seiko to nearby temples and gardens. I remember my first adventure with public bathing. Seiko took me to the baths in the hotel and she and I were there in a tub that was about twenty feet square, about four feet deep . . . with some fifteen others of mixed ages and genders. I was terribly self-conscious at first, but then I got used to it and paid almost no attention to the others, as they paid no attention to Seiko and me. I was growing up. When the week was over and I had to leave, she and I promised to write, to stay in contact, maybe even to see each other again. But neither of us really believed that old lie. She was crying when I got on the train to take me to the airfield, and I wept a few adolescent tears as well. I did write her a letter after I got back, and she responded. But that was the first and last time.

Chuck Cavallero arrived in our platoon just after the war ended, and we soon discovered a similar interest, writing songs. I’d been dabbling in song-writing ever since I was about fourteen. My first song, “Time Will Tell,” was a typical song about unrequited love, written by a typically romantic young man.

Chuck and I collaborated on quite a few silly songs, usually with him writing the lyrics and I the music. I remember how we planned to write the book and score for a Broadway musical, had three or four of the planned songs written. But we never got around to the others, or the book. I planned to write instrumentals with such pretentious titles as “Study in Chartreuse,” “Perambulation,” “Sans Amour,” “Traffic Jam,” “Benny’s Blues,” and “Theme for Despondency,” but never got around to actually doing any of them. I think I was an idea man who best developed ideas for others to accomplish. Or maybe I’m just lazy.

Sometime just before I was sent home I was given a mini R. & R. to a camp not far from where we were stationed. It was just an overnighter, with no girls to be had. I ran into an old acquaintance there, private Dutch Erickson, a pledge brother from that wasted year at the University of South Dakota. He shook my hand and said he was glad to see me, but he was nervous about something.

Later he admitted he felt really guilty about a $40 poker debt he’d owed me from a game back in the Phi Delt house. He paid me and we both felt better. I had $40 I didn’t expect, a sum I couldn’t even remember being owed. One of the peculiarities of life in Korea was that we didn’t really pay much attention to money. Our pay was mostly transferred home. What we took for the few purchases we made there was in scrip, that funny Mickey Mouse money about as real as Monopoly chits. I remember lending a chubby-faced Swede from Minnesota $300 so he could buy his girl an engagement ring. He left Korea for Minnesota and I never heard a word from him. Odd that at the time it didn’t particularly bother me. As I said, money in Korea wasn’t really money, and I, at twenty, didn’t have a very good grasp of values. Those three hundred 1954 dollars would be a lot of money today.

Sometime in the spring of 1954 our platoon was sent south to act as a small aggressor force in a weeklong war game. We were supposed to set up a camp at the top of a mountain, and when the troops worked out our location and came to attack us, we were to hold them off. The ammo was all blanks, and we didn’t have nearly as much to do as the troops going through the game, so I guess it was a good assignment. After it was over and we were down the mountain again, I ran into a Mobridge acquaintance, not one I wanted to see because he had always been such a pain when I knew him in high school. Douglas Clifton. Dougie. The one who always used to hang around, hang on, want to be one of the guys but who could never be one of the guys. We never wanted him around but he was always there and no one ever had the heart to tell him to get lost. It didn’t take us long to catch up on Mobridge news and I never saw him again after that, since he died not long after returning to Mobridge.

I remember looking out across a valley one spring day in 1954, thinking what a great spot it would be for a golf hole. I could see the design in my mind. I really missed golf and knew it was time for me to go home. Golf was always the catalyst in sending me off in new directions in life.

In late June I got the welcome news that I would be trucked to Seoul and flown to Japan to board a ship leaving from Yokohama, almost the exact same route that brought me to Korea. We never had any stormy seas on the return, and I never got seasick. But the two weeks dragged until we finally put in at Seattle, boarded a train that carried me across the Rockies to Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Camp Carson, where I received my honorable discharge on July 15, 1954, after serving one year, nine months, and twenty-three days in the infantry. I was a Tech Sergeant who had earned while in Korea the Korean Service Medal with two bronze service stars, the United Nations Service Medal, the Combat Infantry Badge, the National Defense Service Medal, and the Good Conduct Medal. I was twenty years, seven months, and seventeen days old. And I still didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life.

POST-KOREA & COLLEGE

While in Colorado Springs I bought for $40 a gold ring set with an artificial ruby. I wore that ring religiously for at least thirty years until the band broke and I put it away. Rosalie had it fixed one Christmas and I’ve worn it off and on ever since. But it fits my left ring finger, not my right, and I have to take my wedding band off to wear it, a move that Rosalie doesn’t care for.

I took the train from Colorado Springs to Mobridge and got there in late July. One of my first moves after I greeted my parents and changed out of the army clothes and into civies was to hit the bars, looking for old faces, old friends, looking really for Norma. I wound up at the VFW club on the east side of Mobridge, out near the airport. I walked in and the place was smoky, smelly, and loud. But there in a booth on the other side of the dance floor was Norma. She saw me just as I saw her and that was magic. Or maybe it wasn’t. I tried to figure out which it was in that story I referred to earlier. She was no longer attached to the person of the Dear John letter. She was not attached to anyone. We danced, we looked at each other, we didn’t say much, we didn’t need to say much. We left soon after I got there and went to a dark place on a country road and renewed our acquaintance. Tears were shed about our breaking up the year before, words were said about being together forever, parents were going to be told. The banns would be published that Floyd Jerome Travis and Norma Jean DeSart would be joined in holy matrimony. It was that swift. And it scared me silly. We spent almost the entire next week together. Her sister Connie told me how happy she was about our news. Her parents congratulated me and gave me that doubtful look. Norma suggested we have a picnic at the river and I agreed, but I was feeling less and less like a lifetime commitment to her, or to any other human being. It must have shown in my behavior. We had the picnic but she knew something was wrong and asked me what it was. And I stammered out my confession that I just didn’t feel it was a good time for us to get married. She wept voluminously but she didn’t get angry, just confused. And that was the end of it.

The end of July, 1954, I went to work for my brother Bob in the meat department of the Piggly Wiggly store my dad and two brothers had built on the highway between First and Second Avenues West. The move from Main Street to this new location happened while I was in Korea. My dad had had a series of heart attacks while I was overseas and was no longer working in the store, but Bob, Dick, my father, and my mother were equal shareholders, with Bob in charge of the meat department and Dick the produce. I was going to learn how to be a butcher, a meat cutter. It would be a backup skill in case I never got around to figuring out what I wanted to do with my life. I learned how to cut up chickens, how to cut up hind and front quarters of beef, how to meet and serve the public from behind a meat case.

Thank God I never had to learn how to slaughter the cows and bulls and pigs we bought live and then had delivered to the slaughter house down by the Missouri River. Bob had gone through that particular schooling when he was a young man just back from the West Coast, under the tutelage of Pete Paulson and Tony Ritter. Oh, what an awful place that was. I was there a few times as a boy. I don’t ever remember having to witness any of the actual slaughter, but I heard about it and could envision it in all its awfulness. The slaughterhouse (and yes, that’s what we called it) was located straight south of Mobridge, about a mile from town on Fourth Avenue East. Across the tracks, past the dumps, until you ran out of road. Then a right turn into the place. The house itself was a gray, weathered building about a hundred feet from the riverbank, with holding pens to the north and east. Pete and Tony would drive a beef cow or a pig into the pen just north of the house, shoot it in the head, slide the carcass into the house through a swing door and onto a concrete slab with a blood gutter running south and into the river. Here they would skin and gut the beast, hook it and winch it up in the air so they could halve and quarter it, wash it off before sliding the quarters on a metal trolley system to the waiting pickup to be hauled to the store for refrigerating before being cut into various cuts, the less desirable parts being ground into hamburger or ground fine for bologna. I remember stories about the West-River Sioux coming down to the river to eat the fresh intestines still warm from the carcass, squeezing out the cow shit and then cutting it into mouthful-sized sections about six inches long. It was an awful school for a young man and I wanted no part of it. I’d have had to say goodbye to meat cutting if that part of it had been a requirement.

I worked forty hours a week for about $50. But I was learning a trade. We had a long-playing tape machine that played Sinatra and Gleason for hours at a time. I met my future wife, Rosalie, there when she was selling hotdogs and Coke in some kind of high school promotion. She had just finished her sophomore year and was a young beauty with blond hair in a ponytail down to her waist.

But I looked beyond her. Frankie Sheehan was working at the store, and she was a good friend of the next female in my life, Mary Ann Lay, better known as Bugsy. She and Frankie had just graduated and I think Bugsy had set her sights on me almost as soon as I got to town. That relationship was about as on-again, off-again as it could be. She and I would fight and make up every other day. Her parents weren’t at all thrilled about their daughter going out with a man so much older than she was. I was, after all, nearly twenty-one, a veteran of a war, and probably highly experienced sexually; she was only eighteen and still a virgin. We were together for most of the rest of the summer fighting all the while. We must have broken up on more than one occasion because I remember necking with Frankie at one of the riverside chicken barbecues Pat Morrison used to put on. I remember more than once necking with Virginia Schirber. That summer was one of learning the art of cutting meat and spending all my nights out drinking and partying. I spent most of what I earned, but money wasn’t a concern to me since I still had quite a bit in savings from my eighteen months in Korea.

Then it was fall, and Bugsy and Frankie and most of my partying friends left for college. I think Bugsy must have gone to Aberdeen to Northern State, which was only a hundred miles east of Mobridge, so she was home nearly every weekend. We must have continued our battles for the rest of the year. But I knew it was only temporary and so did she, because my plans were to work until the end of the year, then go to New York to meet my army friend, Chuck Cavallero, where he and I would collaborate on songs and win fame and fortune in the big city. And there was no room for Bugsy in that plan.

I remember the night of my twenty-first birthday, borrowing my dad’s new Cadillac to go out carousing. I had done the usual pre-midnight bar hopping looking for friends or action, apparently really looking for Norma DeSart. After midnight I then began the rounds of the after-hour clubs. I was at the Bridge Club and someone told me that Norma had been there and was now on her way to the Country Club north of town. I jumped in the Caddy, with too much alcohol in my system, and drove too fast toward the Country Club. My route took me onto the gravel road that went north along the river just before Dead Man’s curve and the hill rising east out of the river bottom to Mobridge. I was going much too fast and when I spotted the right turn to go east I slammed on the brakes and began fishtailing in loose gravel, finally winding up flipped over in the right ditch, my engine still going, lights still on, the car upside down like a beetle. I turned off the engine and the lights, crawled out of the car and started the long walk to Mobridge. Dione, son of Shaky, Jandle, who was out there in his cab, spotted me along the way and picked me up and drove me home. Shaky Jandle was a Mobridge barber with some sort of nervous affliction that caused his hands to shake almost uncontrollably. I always avoided haircuts from Shaky.

I crept in my parents’ bedroom to tell them what had happened, but my dad was having another bout of chest pain and neither of them was in the mood to give me any sympathy. The next morning he had someone go out in a wrecker to get the car, which was taken to Davidson’s garage to be fixed. He and his insurance man, Jim Rothstein, were old buddies, so they arranged something plausible to explain how the accident had happened. It wasn’t the first or the last time that Jim would have to come up with some kind of explanation for one of my automotive booboos. The car got fixed, but I don’t think it or my dad were ever quite the same. Just one more in a long line of disappointments from his youngest son.

As long as I mentioned Jim Rothstein and his handling of my accident claims, I might as well explain some of the others. The summer between my sophomore and junior years I was working for my dad as a delivery boy. I took grocery orders in a pickup around to people’s homes. It was a job I loved to get done as fast as I could. I hadn’t yet learned that old truism about haste making waste. I parked the pickup on the west side of First Avenue West, facing south, no others cars on the street, rushed to the back door with my box of groceries, delivered them, rushed back to the pickup, put it in reverse to do a quick reversal of direction to make a delivery up north. Smashed into the front end of someone’s car, someone who’d parked there just after I rushed around the house to make my delivery. I never noticed it behind me, never even thought to look, never glanced in the rearview mirror to see if anything was back there. Jim didn’t really understand my explanation of how it happened. How could I, as I came around to get in my driver’s side, not have seen a car parked right behind me? I tried to explain how I was so intent on my deliveries I simply didn’t see it. He just shook his head. But he made it right in his report.

Two years after my unfortunate flipping over of my father’s new Cadillac I was in my second year at USD (my third, actually, if one counts that early effort as being really a college year) and I had by this time bought a green Pontiac. It must have been in October or November of 1956 because I remember the weather in Vermillion as being semi-cold but with no snow on the ground. I’d been out partying with a few buddies, and they’d introduced me to rum-and-Coca-Cola, a drink with which I was unfamiliar, but which I soon embraced as an old friend. I then decided I had to meet someone else in another part of town, and rushed to my green Pontiac, drove it too quickly, decided to take a shortcut behind Vermillion High School. There were several fifty-gallon drums at the back of the school in which paper and other refuse was being burned, not high flames, just simmering. It was now early evening and quite dark and I could see the flicker of glowing ashes as they billowed up from the drums. I was going too fast and the shortcut was muddy. I tried to make a slight turn around the burning drums but instead slid toward them and then onto them. When no amount of backing and forwarding got me anywhere I realized I was high-centered on the drums. I got out of the car to see what could be done about it and immediately noticed that the hot smoldering drums were causing old oil and grease to drip onto the flames. Not a good sign. I opened my trunk and took out a nine-iron to use to dig beneath the drums to get my car free of them. No matter how I dug, the flames kept building and I knew I wasn’t going to get it off. I took my golf bag and clubs from the trunk and set them well away from the car and ran to the fire station several blocks down the road to report the fire. The fire trucks came with sirens blaring, people gathered at the site to witness the fireworks, I stood in the darkness with my golf clubs. I remember hearing people wonder aloud how such a thing could have come about, how anyone could have been so stupid as to have driven over burning garbage cans. I didn’t say a word. The next day I called my dad to explain what had happened, and he called Jim Rothstein to try to explain what had happened, and Jim called me to hear what my version of the story was. I could just imagine him shaking his head in wonder at this strange son of his friend who had so often made his life as an insurance adjuster so complicated. He filed the claim as a fire loss, and I got back enough money to then buy a light blue Chevy.

End of auto-accident sidebar and back to 1954. December passed without any other incidents, and just after Christmas I flew to New York to meet Chuck and begin life anew.

I flew in to LaGuardia Airport in New York City on December 30, 1954. I remember the plane was above a layer of thick clouds and when we began our descent we headed down into what looked like a funnel in the clouds, with black smoke issuing forth. That was my first view of the Big Apple. I landed, took a train from Pennsylvania Station to Philadelphia, spent the night in a Philadelphia fleabag, and New Year’s Eve at Chuck’s parents’ house, eating my first truly Italian dinner in a truly Italian home.

On January 2, Chuck and his brother Joe and I took the train to New York City. Together Chuck and I were going to write music, stand Tin Pan Alley on its ear. Of course neither of us knew what he was doing. He was a dancer training for Broadway and I was along for the ride. I’m not sure what Joe was doing. Finding work there and sharing the expense of an apartment. Chuck was going to audition for Broadway musicals and I was going to take singing lessons, maybe even go to Juliard to learn more about music and the writing thereof. When I first met Chuck in Korea, he discovered my interest in song writing, that I’d been doing it sporadically since I was about fourteen. Together we wrote about a dozen, he doing the lyrics and I the music. None of them were very good, but they weren’t bad, and there were any number of ballads being sung in those days that weren’t any better than what we were writing. I specialized in the 32-bar formula songs—ABAB or AABA. But since we never really sold anything, songwriting doesn’t qualify as a job.

In order to feed and house ourselves we had to have real jobs. The first thing we did after arriving in the big city was to look for employment. We answered an ad with the Washington Detective Agency, which was looking for young men to train as private detectives, private eyes, like Mike Hammer or Michael Shayne. Now that sounded like a job. That sounded romantic enough for two young Korean veterans. We were interviewed, we were hired. The owners, two brothers straight out of Damon Runyon, wanted us to go into several different White Towers in Manhattan to keep our eyes open for any pilfering by the other employees or any scams for stealing from the chain’s owners. White Tower was a large chain of fast-food stores with thousands of locations up and down the East Coast, so any pilfering became a huge amount if it happened throughout the chain. We agreed. But what we were hired to do wasn’t quite legal, so we received wages from White Tower, and then on weekends we would meet one or the other brother in a downtown hotel lobby and he would surreptitiously slip us cash for our week’s efforts. So we were double dipping, one dip under the table without any state or federal taxes. Between the two salaries I was taking home well over a hundred dollars a week, not bad for a young man in 1955. They even told us we could work weekends, tailing people. I never took them up on the offer, but now I wish I had, if only for the fun of reminiscing about the silliness involved.

I worked in three different White Towers in Manhattan but the only one I really remember was the last one, right across the street from Madison Square Garden. I learned that some of the employees were half-bagging pots of coffee, the first half for the company, the second half for them with the money not rung into the register. The company kept very strict records of how much coffee was made by the number of packets used, each packet supposedly making one pot. The employees were selling weak coffee and taking half the profits. That may not sound like a lot, but if each White Tower sold thirty pots of coffee a day for about a dollar a pot, but only half that number was going to the company, it could total thousands of dollars a day considering how many White Towers there were. Another scam was to take home the coffee creamer and substitute half-and-half, again, not a very flagrant scam, but over the course of all those White Towers, a scam to reckon with. So every weekend I’d meet surreptitiously with one of the Washington brothers and make my report, collect my extra wages, and go home.